ESSAYS

A CONVERSATION WITH LENA HERZOG

By John Bailey, ASC

Published: December 19, 2011

There was an electrical power blackout the day that seventeen-year-old Elena Pisetski first encountered a collection of jarred fetuses in the galleries of St. Petersburg’s Kunstkamera Palace, where an eerie light seeped in from the windows. Pisetski was a student at the university’s Philology Faculty located on the embankment of the Neva River, next door to the beautiful aquamarine-colored mansion housing the scientific specimens of Dr. Frederik Ruysch. Ruysch was Dutch, one of the legions of seekers of new knowledge who, during the age of exploration of the New World, collected thousands of related and unrelated artifacts from his native Holland as well as from distant lands, into what were called Wunderkammern (Cabinets of Wonder).

These antecedents of today’s natural history and fine arts museums became not only repositories for scientific study, but tourist destinations for the elite curious and the idle rich. In 1688, a sixteen-year-old Russian prince, working on Holland’s wharves, saw the natural and biological artifacts of Dr. Ruysch’s Cabinet of Wonders and became fascinated with his rich collection. Years later, as Peter the Great, he acquired and moved the collection to the new capital city he was building amid the swamps of the Gulf of Finland.

Pisetski already knew of the mammoth array of biological specimens, numbering some 2000 items. Some of her professors used to joke that if their students didn’t study, they would be “pickled” and sent next door for exhibition. The czar’s old, much neglected “wonder rooms” had few visitors in those late days of the Soviet Republic; many generations of visitors had long considered the jar’s contents to be morbid or horrific, and the rooms were often closed, labeled “under repairs.” Many similar European collections of the unborn were simply mothballed, a notable exception being the Henry Welcome Museum in London.

Pisetski stood before the jars, the room’s crystal chandeliers refracting the late afternoon light of the Kunstkamera windows. Several decades later, in a public interview with Lawrence Weschler at the New York Public Library, and now known as the photographer Lena Herzog, she recalled:

There was no terror in me at all. I did not experience horror because when I first saw the preservations, they looked like creatures from another world: completely silver, and like they were shining from the inside because of the way they were lit.

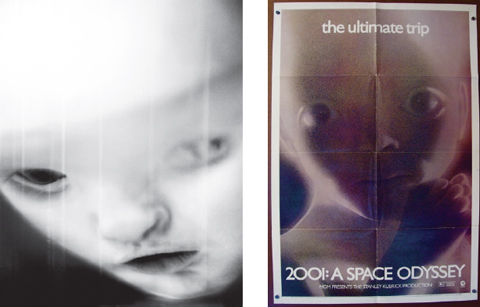

A number of critics have likened this display of malformed fetuses, conjoined twins, hydro and micro-cephalics and other human grotesqueries, to the embryonic star child hovering in the cosmos at the conclusion of Stanley Kubrick’s film, 2001.

But for many of the “natural philosophers” (as the developing discipline of “scientist” was still called), the cabinets of wonder provided the then principal body of empirical evidence of the worlds of botany and biology. As oceanic travel expeditions and closely observed laboratory work in the early nineteenth century began to replace philosophical speculation as to the nature of the world’s flora and fauna, these by then antiquated cabinets continued to be treasures.

A profusely illustrated photo history of these installations is by Patrick Mauries:

But the cabinets did not disappear and had a presence well into the modern scientific era. Herzog explains it:

Cabinets were still being made in the XIXth century even though the split between science and humanities occurred in peoples’ minds and education, and the Cabinets themselves split into art history museums and natural history museums by then. I think constant encounters with failures of the body inspired a lot of mythologizing and theorizing. Now we are very disconnected from death, birth, miscarriage through a series of procedures at the hospitals and maternity wards. But in those days, until recently, seeing dead animals, babies, even adults, was fairly common. Some of the embryos did look like animals, so the idea was digested into one of the theories floating at the time which also made different creations share features and establish hierarchies.

A drawing by Ernst Haeckel illustrates one aspect of a theory of life called “re-capitulation,” one of the many that strove to show common links in the stages of anatomical development.

On NPR program Science Friday, Lena Herzog offers a four and a half minute audio and video slideshow that presents the importance of Dr. Ruysch’s work; it contextualizes ideas of the theological and scientific wisdom of the time.

Herzog’s succinct comments are a crucial prelude to an understanding of the photographs she presents in her book, Lost Souls. The pictured fetuses were called “lost souls” because they were outside the construct of what a human being was generally defined to be. Many of them were not full term and had been removed from dead mothers; others were at term, but stillborn or had died within a matter of minutes, as they were too deformed to make sustained life possible. In the theological worldview still dominant in the Roman Catholic and Orthodox religions, these beings could not be relegated to a place in hell, purgatory, heaven or even to limbo (the uneasy but eternal placeholder for non-baptized innocents); they were simply “lost.” What could more symbolically represent their uncertain status than floating in jars of preservation liquids?

An exhibition of Herzog’s Lost Souls photos, made in some seventeen different Kunstkammern (including Leiden, Utrecht, Vienna, St. Petersburg, Turin, and Amsterdam), as well as her allied photos of an “orchestra” of mice skeletons and other anatomical anomalies, took place in the summer of 2010 at NYC’s museum of photography, the ICP.

Two blocks south, at the New York Public Library, Herzog appeared in conversation with writer Lawrence Weschler. Weschler is a fascinating polymath whose interests (and books) span the worlds of art, literature, science, and popular culture. He once interviewed a group of artists and scientists for a New Yorker piece about the special “light” of Southern California. He and I discussed the light of Los Angeles as captured in Hollywood movies. Weschler also wrote a short but engrossing book about a contemporary Los Angeles museum (Museum of Jurassic Technology) and its founder, one patterned along the concept of the cabinets of wonders:

Graham Burnett introduced the New York Public Library conversation with an historical purview (he also wrote the introductory essay for Lost Souls.) The library videotaped the eighty minutes long discussion and put it on their website.

After his introduction, Burnett presents a slideshow of Herzog’s images starting at 19:00. It fades out and up to directly reveal Weschler and Herzog at 21:30. The remainder of the video is a dialogue between the two that feels like an overheard intimate conversation.

nypl.org—Lena Herzog in Conversation with Lawrence Weschler (audio/video) link

Herzog offers an explanation of Frederik Ruysch’s decision to preserve the human specimens for which he dedicated so much of his career. This commitment was so complete that he became a licensed midwife, working to inform and reform the role of the midwife as a legitimate profession. Herzog quotes his rationale:

In botany, all the questions are simple, and so are the answers; it is in anatomy where the mysteries are.

The mysteries arise not simply out of those anomalous beings that became the objects of study in the jars, but of the Age of Enlightenment’s efforts to discover and define the nature of human development a full century before Darwin and his On the Origin of Species. Competing arguments among natural philosophers advocating ideas of “preformation,” “epigenesis,” or “recapitulation” all had passionate advocates but they were speculative rather than empirical. It was the physical evidence in the preservation jars of Ruysch and other anatomists that stood as vibrant but mute witnesses.

Herzog’s photographs of these wondrous beings stand by themselves as works of art, but it is also with an understanding of their scientific context that they assume a dimension of awe. This is the full perspective that motivates her work.

It is one thing to see these images in her book or even framed on a gallery wall. It is an altogether more moving experience to sit next to her as she opens a box of prints and presents them one at a time as a sacerdotal offering. Here you can see and almost smell the rich textural depth of the prints, prints made from negatives developed with an old and complex process that Herzog discusses in an interview later in this essay.

Herzog does not claim to be a pioneer in photographing these specimens; the documenting of anatomical specimens goes back to photography's earliest decades. In a recent email she wrote me about this history and of her own imperatives in deciding to do this body of work many years after being exposed to the exhibits while a student:

Actually there has been a long tradition of photographing congenital anomalies. More recently, Rosamond Purcell has done a lot of work on birth defects before me. But neither she nor I were first on the scene. Some of the images I culled in my research date back to the 1840s. What I wanted to do though was not a medical report or a perverse fascination into the tragic dead ends at life attempts, which is one of the main reasons why I never concentrated on the shocking. I made sure that the most disturbing was kept out of the frame not because of a prurient objection; it's just not interesting to me. Trying to make shocking or perverse images is pointless, very boring and infantile. I was more aligned with the philosophical, poetic and existential aspects of the subject. What constitutes norm or humanness? How did we go about mapping the world and its boundaries? What is the nature of preservation? How does that practice transform itself from collection of objects to preserving a moment in time, "freezing life"? What does it mean for me as a photographer to look at those preserved still lives? In what sort of a corridor of mirrors [do] I end up? Those are much more interesting questions and, luckily, they remain. . . They are so big and heavy; they are mostly for my own "internal" use. These were the very questions the original Cabinetmakers had themselves. So, it is natural that they'd simmer to the surface—the themes had always been there.

A few weeks ago, Carol and I were invited to have dinner with Lena and her husband, Werner, in their Laurel Canyon home. After dinner Lena opened several portfolios of prints from Lost Souls. Later, she showed me her darkroom, converted from a garage space. Prominent were two large format printers and a top-notch clutch of chemicals, trays, and sinks—all tools of a master printer’s alchemy. The smells were redolent of an age now slipping away from us, a photochemical one, increasingly replaced by one of non-sentient computer/printers. Seeing the tools of her trade in their manicured array prompted me to consider talking to her about the physical dimensions and techniques of her work; it also proved to be a fertile introduction to her aesthetic intentions, reflected in the sometimes unwieldy, even “temperamental” machines of her art.

Here is the interview:

What camera and format film do you use?

My cameras: Leica M6 (35mm), Hasselblad XPan panorama (35mm which uses two or three frames), two Linhofs (four by five inches, and six by seventeen—the panorama), an old mahogany wood four by five Deardorff, an old medium format six by nine Fuji and another, also medium format, old six by seven Pentax (the only camera which is not my preferred parallax), two suitcases full of lenses. I like to shake myself out of old habits and shift focal depths, re-adjust the way I see things. All my working cameras are analogue, but I do have a digital Leica for research and sketching, and a MacBookPro and an iPad for digital archiving, books and shows layouts.

You seem not to have fallen in love yet with digital cameras. Why?

This is a long talk people should have over a good amount of coffee and liquor, after having banished from the room old fake debates about mutually exclusive choices. I do not see the analogue vs. digital debate as an old vs. new struggle, just as I do not see progress as a simple assembly line on which the latest thing is the best. What’s good for the makers of the latest gadget is not always good for us because the latest tends to be easier and makes us lazier and more stupid. Digital cameras delegate our decisions to computers and they are not capable of nuanced intuitive and poetic choices. More seriously, ideas are nothing unless they are fundamentally intertwined with craft.

Analogue allows building a three-dimensional sculpture—a negative, which is an object, rather than a file; it demands an interdisciplinary competence in optics, chemistry, equipment and it allows a lot of room for intuition, what Sherlock Holmes called “the scientific imagination”. Real poetry happens in the margins of the medium—the unpredictable space where error and magic occur. The margins in analogue are all about light; the margins in digital are all about pixilation. The former thrills me; the latter is a gimmick to my eyes. But it’s a false dialectic. At least for me, digital and analogue have different purposes.

Have you considered scanning digital files to film or vice versa?

When I create my print it is first and foremost an object; then, in other incarnations, it becomes a file, used for a book, a website upload or some Internet version. Digital is unparalleled as a data aggregate and a delivery system. Analogue—as a tool of and for craft.

You have high regard for the pyrogallol developer that you use, despite its reputed instability and toxicity. You said it produces “three-dimensional negatives.” Can you expand that thought in terms of how it “looks.” What are its distinctive properties?

You see the physical profile of the pyrogallol developed emulsion with the naked eye when you tilt the negative at a slight angle—it looks like an engraving plate not your average dip-and-dunk neg. Pyro mimics an intaglio (groove incision) process by creating halos on the edges of objects. In fact, you can create an effect of a cutout by printing at the highest contrast.

On the other hand, pyro staining allows you to make an image that is like a cloud or a low contrast daguerreotype. You can make incredibly delicate prints with infinite subtleties.

When and if, which is a big “if”, you find the few of my fellow mole rats (printers) and ask them about their first experience with pyrogallol, or, as we call it, pyro, you will hear stories equal to those of apparition or revelation. In fact, it’s better than any revelation. You see miracles in the negative the moment you get it out of the wash: the hyper definition in the highlights and the shadows, the sharp edges of the outlines of objects, the stain. Simply nothing gets past it. Pyro catches everything. But as anything great it has a flip side—a price you pay for volatility. Sometimes you get what looks like a hairball my cat throws up. I still love my cat. And I do love pyro even though sometimes I have to throw a great image away because of a “pyro hiccup." I shall still keep working with it.

It is a process that, though used by Edward Weston, fell out of favor after WWI, only to be revived in the 1980s by Gordon Hutchings, who formulated a more stable version called PMK. Is this what you use? Is it a prepared formula or do you make it up yourself like a chemist?

It’s exactly what I use. You know, some people would say to themselves, “I wonder what God would think about it." I say, "I wonder what would Gordon think about it," especially when I have pyro trouble.

Is pyrogallol a developer for negative film only or is a version of it also used for darkroom prints? And if so, do you use it for both developing and printing? And what about the print paper?

I have only used it for negatives. My printing has a lot of various recipes and paper preferences.

How do you approach making a print?

I think of it when I take my picture. It starts at exposure. Then, when the negatives are done and contacts are made, I start testing and tack some test prints on my wall. When the folio starts building up, I think of it as part of a body of work but also, separately on its own terms. I make a few more tests and then—the final print. If I think it is a keeper, I print an edition of it.

How time intensive is each print?

Hard to say. I have produced twenty prints a day under pressure. But that is no good. Five prints a day is a decent day’s work.

Is each print “hand made,” that is, manipulated by you as an individual piece of art, or do you have a master negative with all your notes built into it, and then create what are essentially one-light prints? In motion picture printing we create an interpositive or a digital intermediate that embeds all the corrections.

Each print is individual, “hand made” by me, no interpositives, no intermediates. But I take copious notes on what each print needs and can make a full edition easily after the first print is done.

Do you continue to make photochemical rather than digital prints because you believe that they are aesthetically superior, or is there also a human crafts component to it?

It is both aesthetically superior and a human craft component adds to its value. However, I must stress, that I am talking about master prints, not average run of the mill prints. The best digital prints are better than mediocre silver prints, but nothing matches the best silver prints made by a master printer.

When I imagine the world of art I dream of it as a warehouse of objects rather than a giant hard drive. Ultimately, my affinity for analogue comes from an utterly unsentimental preference for a “sensuous” experience and here I use this term advisedly, I mean “having to do with senses”—seeing, first and foremost, but also a palpable tactile feel of a print, even smell. I love to see and feel a great Steichen print. That recent show at the Met “Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand” still makes one think and dream, and that’s the point of anything meaningful.

I also believe that a good piece is a combination of ideas and craft: that they are so deeply intertwined they are Siamese twins sharing vital organs including the brain.

You showed me your two darkroom printers. Can you tell us what they are, how you acquired them, and why it is so important that they are aligned as they are? You explained that you use lasers to set them. How much work is required to maintain the printers?

Some ten years ago my fellow mole rat, a great master printer, Marc Valesella, told me that the Los Angeles lab working for NASA and the CIA was throwing out their old analogue enlargers that Durst and Beseler custom made for them. Funny, they were once used to blow up spy satellite images of Russia. Now, I—a Russian, am using them to print snowed in landscapes and three-headed Cyclops. These enlargers have APO lenses and they can be dead mounted to a wall rather than stand on flimsy legs as all commercially sold enlargers do. I got these extraordinary machines for a few hundred dollars—each, even though they must have cost thousands when they were first ordered thirty years ago. I use ZigAlign laser equipment to align my lens and negative planes to the adjustable easel table, which puts the entire paper plane in focus rather than just one part of it. That means that the whole image is in focus and that every grain gets the best treatment.

It is good maintenance to dust and oil your machines and to align them once in a while, say, once every few months. When there is an earthquake, including small tectonic adjustments that are frequent in California, or when there is construction very nearby, I check for parallel alignment. Even with a soft focus in the image, grain has to be in sharp focus in the enlargement stage to preserve the quality of the print.

This is not a technical question but an aesthetic one. In an interview Lawrence Weschler drew a parallel between Dr. Ruysch doing his laboratory work in a darkened space and the absolute darkness you require for the printing you do. I was struck by another parallelism, one that I have not heard you discuss (I may have missed it)—and that is the notion that as a philologist you are required to do close and analytical textual scrutiny. There is often a kind of taxonomy involved in this study in terms of building up information fragments to form a whole text. It occurs to me that this philological method also informs much of your photographic work. Within any body of your work, you create a photo essay or catalog, even a hierarchy, of images. And on a broader scale you are attracted to a single subject or field of study such as bullfighting, and apply a kind of taxonomic focus to your photos. Maybe this is all too obvious to respond to. But if not, I would love to have you discuss it.

I studied languages and linguistics because what I really wanted to study—philosophy—was unavailable to me in the 1980s USSR. And by philosophy, I mean the history of ideas; I was not keen on Marxism and Leninism which was all we could get our hands on, at least legitimately, at the time. When I immigrated to the United States I did study philosophy. My thesis was “Scientific Revolutions. Comparative study of Thomas Kuhn and Paul Karl Feyerabend.” I have always been fascinated by the structure and shifts of ideas, paradigms, attitudes and philosophies. I love thinking and dissecting multi-level problems, but that is all just preparation before a shoot.The shoot itself is pure delight and hunting time. That is when everything you are coalesces in a fraction of a second.

Roughly speaking, the world, especially the world of visual art, falls into iconoclasts and iconophiles, the skeptics and the enthusiasts. The former do not trust their eyes, the latter exalt in what they see. I love reading iconoclasts and I am bored to death when they are making pictures even though nowadays they are all the rage and they are setting trends in the art world. By definition and by inclination they are incapable to feel the thrill at the sight of something thrilling because they are iconoclasts at all times. A clinical shot next to a giant caption is just that: a clinical shot next to a giant caption, that’s all. It is second-rate journalism accompanied by third-rate pictures as one very smart editor once told me. To avoid it you do not have to put your critical thinking on hold. A lot of research, thinking, writing and, yes, taxonomy, goes into my every project, which is why an average time span for each is five to seven years. Luckily, I have some eighteen of them going at a time. Preparing and developing concepts is a given, not a badge of honor, and though it’s ok to share your thoughts in an interview like this one, I always found it pretentious when artists include their sausage making as part of the shows and books, and worse, when they make their sausage making the piece!—As if they are eager to become their own very impressed (by themselves) critics. What I am saying is that the iconoclast in you should do the work before and after the shoot: during research and then---in the darkroom. The iconophile has to do the shoot.

The simple truth is: at the end of the day each picture has to stand on its own. It has to thrill, haunt whoever is looking not because of a pompous concept that you plastered next to it but because of it—the image. And if it does not burn your soul when you are taking it, it will not burn anyone looking at it.